![]()

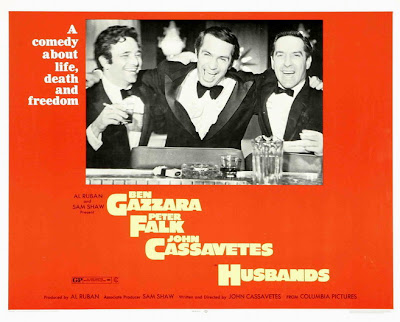

This year was dominated by two writers for me. Having been introduced to the elderly London detectives Arthur Bryant and John May towards the end of last year in The Victoria Vanishes, I read a further 8 novels featuring the duo at the beginning of this. They’re such hugely appealing characters, bringing the values of post-war optimism and hope into a darker and more complex and venal present. May’s tact and ageless elegance and charm perfectly balance Bryant’s old from an early age gruffness and instinctively anti-establishment egalitarianism, a becalming John le Mesurier to his friend’s raging, eccentrically autodactic Romantic soul. As befits a writer who also has an affinity with the darker end of the fantastic genres, the detectives’ investigations within the Peculiar Crimes Unit generally have an aura of the strange and the supernatural, although seldom stepping beyond the bounds of the rationally explicable (although Bryant does gather some important tips from his scatty, Margaret Rutherford-esque occultist friend Maggie Armitage). The novels also explore a rich seam of London lore and urban legend, often centring on a particular aspect of the city (its pubs, theatres, sewage systems or underground network). Bryant’s wayward researches allow for a good deal of tangential but fascinating material about the London nobody knows (except Bryant, of course), offering a rather more accessible take on Iain Sinclair’s psychogeographies. These are very much London novels, although the duo do make the odd, rather reluctant expedition beyond its boundaries: a short jaunt down to Brighton (London-on-sea) to consult with a punch and judy man in The Memory of Blood, and an ill-advised trip across a snow-bound Dartmoor in White Corridor, a novel which fruitfully experiments with the series’ form. You strongly suspect that Bryant’s unrestrained (and usually unprompted) expositions of his outlook on various aspects of contemporary politics and society act as a convenient vehicle for the author’s own views (regularly aired on his prolific and always interesting

blog). I’ve yet to read the latest case, The Invisible Code, published earlier this year, and so have that and two more upcoming novels (and a comic) to look forward to next year. Can’t wait.

![]()

I also read Fowler’s Hell Train, his homage to Hammer films and, with its intertwined portmanteau tales set on a train of the damned, perhaps Amicus and Dr Terror’s House of Horrors too (with a bit of 70s Cushing and Lee throwaway romp Horror Express added for good measure). If it failed to live up to its initial promise (and, for an avowed Hammer fan, enticing premise of a ‘lost’ script), then it was never less than entertaining. The novel has a story within a story structure, with a scriptwriter trying to produce a story super-quick, adjusting it according to the demands of the producer. The cameo which he adds in to allow for an appearance by Peter Cushing is particularly nicely done. The 2001 story collection The Devil In Me showed the range of Fowler’s writing, ranging from noir to horror, Wodehousian humour to quietly observational character pieces. Particularly fine were Crocodile Lady, in which a primary school teacher returning to the job after many years, follows a child who has been led astray during a school outing through the chaos of the underground with heroic doggedness; and The Beacon, a beautifully balanced tale about connection and understanding in the age of remote digital communication, which resembled the short stories of Katherine Mansfield in its sad ironies and delicate characterisation. Fowler’s childhood memoir Paper Boy was lovely, both funny and poignant, with a hint of melancholia which is perhaps inherent in such reminiscences, with their memories of people and places long gone. With its south east London suburban settings, it also inhabited territory with which I am extremely familiar. Paperboy was a gratifying success for Fowler, and a follow up memoir, Film Freak, taking him into the heart (or thereabouts) of the London film industry, is due for publication in the near future. Another one to look forward to in the new year.

![]()

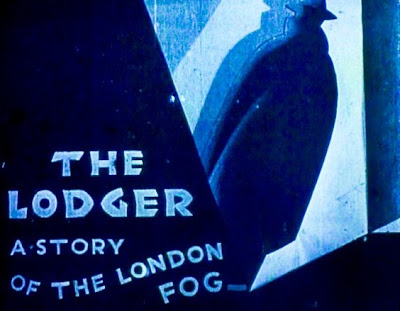

I also read a great deal of Angela Carter this year, which marked the 20th anniversary of her horribly early death. I worked my way through all of the novels, save for The Passion of New Eve and Nights At the Circus, which I read last year. It was particularly interesting to read the early and relatively neglected books, and to find the familiar elements of later books present in nascent form. Shadow Dance, Several Perceptions and Love form what is sometimes thought of as the ‘Bristol trilogy’, reflecting Carter’s time in that city during the 60s, and cast an ascerbic and ironic eye over the aspirations of countercultural drop-outs. The Magic Toyshop is set in Carter’s childhood territory of South London, and presents a 60s world still in thrall to oppressive Victorian values and with an atmosphere defined by decaying gothic-revivalist architecture. Whilst none of these have explicitly fantastical elements, their fascination with the gothic and with masques, role-playing and dark grotesquerie sowed the seed for future fabulations. Heroes and Villains was post-apocalyptic science fiction which might easily have found a place in New Worlds magazine, alongside similarly brutal depictions of social collapse and primitive savagery produced by M John Harrison (The Committed Men) and Keith Roberts (The Chalk Giants) at around the same time. In The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffmann, Carter’s gave her imagination full reign in a picaresque journey through a landscape in which the monsters of the id have been set loose, under the influence of the Doctor’s rays. The protagonist, Desiderio, has a variety of encounters on his travels, travelling with gypsy bargees, performing in an erotic carnival, visiting an extravagantly impersonal brothel with a licentious count, falling prey to cannibals, and becoming a sexual slave to a herd of centaurs before finally arriving at Hoffmann’s castle. It’s an extravagantly decadent novel, consciously drawing on various literary sources, and finds Carter at her most full-blooded, her unexpurgated imagination brought to life with lush, rococo prose. Her final novel, Wise Children, marries Shakespeare with music hall and Hollywood in a bawdy and warm-hearted tall tale of theatrical dynasties and the good life south of the river. I also re-read The Bloody Chamber, which contains Carter’s best known reconfigurations of and commentaries upon fairy tales and folklore. I managed to pick up a copy of the new Folio Society edition, with its lovely accompanying watercolours in a classic Rackhamesque style by Igor Karash, who won a competition to provide the illustrations. A Postcard From Angela Carter by Susannah Clapp was a short and very personal reminiscence of the person whom she knew, whilst Angela Carter: A Literary Life by Sarah Gamble provided valuable analysis of her work, relating it to her life and experience.

![]()

I read two books by Elizabeth Hand, who could be said to be one of Carter’s successors. Generation Loss was a fine detective story of sorts, with burned out punk photographer Cass Neary travelling from her native territory of New York up to a remote town on the wintry coast of Maine to meet a legendary photographic artist, who disappeared into reclusive obscurity many years ago. She comes across a community locked into its own dark Pagan rituals (Hand’s novels often find Pagan rituals and beliefs re-emerging in the modern day), distorted from their origins in hippy communalism. It’s an utterly absorbing mystery, with an engaging protagonist, the drug-taking, heavy drinking Cass, a wiry Patti Smith type wholly out of her element in the wilds of Maine, but finding her way to the heart of the matter with the help of amphetamines, cynical toughness and an underlying passion for her lost artistic vision. The short novel Illyria was a coming of age tale, with its young female protagonist discovering her artistic path within another semi-rural communal set up, an element of the supernatural intruding via a strange miniature stage uncovered in an attic space, which seems to glow with its own footlights, and experience its own microclimates. An entrancing fable of the golden moment of youth when all seems possible, and the world appears to be a stage awaiting your grand entrance. It’s wise but not overly pessimistic in its depiction of the disappointment of potential greatness left unrealised, of the dissipation of youthful energy and excitement.

![]()

There were some exciting new novels from favourite authors, with M.John Harrison’s Empty Space, Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue, Tim Powers’ Hide Me Among the Graves and Samuel Delany’s Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders. Empty Space was the follow up to his previous novels Light and Nova Swing, which saw him produce his own distinctive brand of hypermodern space opera. I read all three consecutively, to better appreciate the sequence as a whole. Light set up Harrison’s fictional universe, which the other novels also inhabit. There are three intercutting narrative strands, one featuring a twentieth century theoretical scientist and grubby serial killer named Michael Kearney (Harrison never dwells on his impersonal murders, which are as incidental to the story as they are to him); the other two set in a 25th century in which humanity has spread out to the far corners of the cosmos, and centre around a rebellious ‘k-ship’ (an interstellar craft which uses the reality warping potential of the new physics) pilot named Seria Mau Genlicher; and wide boy Ed Chianese, on the run in the slums of a corporation planet from the Eva and Bella, the Cray Sisters.

![]()

Light contrasts a dreary present day world on the cusp of the new millennium with a future of almost limitless possibilities, in which different and seemingly contradictory physical laws and scientific models co-exist and can be exploited. In spite of this miraculous sense of endless potential, people nevertheless constrain themselves the same roles in the same old scenarios. They have themselves tailored, or ‘zipped’, or use disposable ‘cultivar’ bodies which provide them with overdetermined sexual stereotypes. Men can have huge tusks, whilst women often go for the Mona package, modified into eternal Marilyns. The corporatisation of human life has been exported to the stars, with a resultant ennui and sense of powerlessness which infects the sections set in the present day. Some opt to spend their time in the viscous proteome of the ‘twink tanks’, like Ed Chianese, dreaming away their lives in manufactured worlds and stories. The corporate governmental expansion into the furthest reaches of the cosmos and appropriation of what it finds there (boldly going in the name fo maximising profit margins) is embodied in their creation of the k-ships. These are fusions of human, machine and something wholly other: ‘shadow operators’ who cluck and worry like over-solicitous old ladies, their disembodied, phantom forms flickering at the periphery of vision. Seria Mau is forever bound to her ship, like a spectre anchored to the site of its death, the ghost wired into the machine from which it projects itself. The scene in which she discovers the pitifully diminished and mutilated state of her body, de- and re-formed whilst she was still a young woman to fit into the ship’s pilot tank, hardwired into its navigation systems, is filled with a terrible poignancy and a furious burning rage at the powers which would use people as so much disposable meat in the pursuit of further power and dominance. Looming above the planets of the ‘Beach’, a marginal interzone marking the boundaries of the known universe, is the Kefahuchi Tract, a radiant auroral rent in the universe which represents a remnant of the mysterious, the transcendentally unknowable, a completely different order of reality. Daredevil pilots, or entradistas, such as Ed used to be, defy conventional physics common sense in order to approach the borderlands, pushing at the bounds of the possible.

![]()

The emergence of the tract has something to do with the advanced quantum calculations of two scientists in the present day, Michael Kearney and Brian Tate, who struggle to continue their work in the face of corporate pressure. Kearney is haunted by a creature he knows as the Shrander, a being which manifests itself as a terrifying ragged figure with a stripped horse’s skull for a head, like something out of an old folk ritual. He kills in the belief that this will keep it at bay, and is a thoroughly wretched creature, despite the fact that we know his theories (the Kearney-Tate equations) will lead humanity out to the stars. In the end, he confronts the Shrander at a place called Monster Beach in America, which evidently corresponds with the Beach on the edge of the Kefahuchi Tract, and is granted a vision of the astonishing beauty of the cosmos from which he has been shrinking. Light is a simply dazzling book, filled with subtle correspondences, linguistic play, anger-fuelled satire, and the display of an almost casually profligate imagination. It’s also extremely deft in its use of science fiction’s potential for surrealism and metaphor.

![]()

Nova Swing grounds the cosmic sweep of Light, limiting things to one planet. This is Saudade, onto which a part of the Tract has crashed in the wake of the events which ended Light. This results in a forbidden zone at the industrial end of Saudade City, which has similarities with the Zone in Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker (again, there are correspondences here, Kearney having seen all Tarkovsky’s films in Light). As in Stalker, it is an area contiguous with the mundane world, and seemingly a part of it with its decaying industrial landscape. But it operates according to unpredictable and surreal (a permanent whirlwind of shoes, for example) physical rules of its own. Vic Serotonin is a guide to this dangerous area, hanging out at the White Cat, Black Cat bar whilst he waits for clients (another correspondence with a film seen by Kearney in Light, this time directed by Emir Kusturica). Other characters in this neon noir novel include Lens Aschemann, a compassionately weary detective who looks like Einstein feels like he’s stepped out of a Wim Wenders film or a science fiction novel by Samuel Beckett; a policewoman technologically enhanced to the point where she can shift into a hyperkinetic blur of motion and lighting, millisecond calculation; treet punk Alice Nylon (the perfect name for a street punk); wasted zone veteran Emil Bonaventura and his tango loving daughter Edith; and barkeeper Liv Hula, Mona packaged Irene, and ordinary Joe ‘Fat’ Antoyne. These three end up joining together to buy out the spaceship Nova Swing and run it as a transport vessel (interstellar truckers). They return again in Empty Space, and Irene provides the heart of the story, remaining possessed of a certain innocent sense of wonder (the state which old-fashioned SF was often said to evoke). She is somehow linked with Anna Waterman in the present day, who was married to Michael Kearney in the first novel, and now lives on her own in the Sussex house she shared with her late second husband. The south downs loom in the background like the Tract. The tract bleeds through into the ‘real’ universe in both times; bodies fuse, interpenetrate one another and hang suspended in space after death, slowly revolving like planetary satellites or galaxies (another Tarkovsky allusion here, perhaps, to the levitating or orbiting zero-g bodies of Mirror and Solaris). Irene and Anna are adrift in the world, but intuitively enjoy moments of simple and direct joy. Anna’s naked nightswim down the Sussex river is the equivalent of the entradistas’ plunges into the Tract. And for the young man she meets outside the village pub, the grand cosmic drama of the far future is concentrated into the experience of watching his hounds racing down a corridor of light when he goes out lamping at night.

![]()

There’s something summatory about these novels. They bring together many of the elements characteristic of Harrison’s work over the years: the juxtaposition of the seedy and defeated with the transcendental; a Gnostic spirituality in which a divine force (often in fearful form) attempts to break through into a devolved world; the use of Tarot cards and their symbolism to indicate the play of chance and recurrent patterns in life; cats and their mysterious otherness; the horse’s skull, which features (in the form of lamb’s skull) in the Viriconium story The Luck in the Head; the New Men, straying from the fantasy lands of Viriconium into this science fictional universe; the seedy séances held in dilapidated suburban houses; the colourfully poetic naming craft carried over from the 1974 anarchist space opera The Centauri Device (Light’s La Vie Féerique, Karaoke Sword and Touching the Void – the latter a link with Harrison’s love of climbing – and The Centauri Device’s decadently Aesthetic Atalanta in Calydon, The Green Carnation and Driftwood of Decadance – Wilde and Swinburne in space); and the constant theme of tawdry, prefabricated fantasy and escapism as a trap, and the metaphysical need to find one’s own way of pushing against the limits of environment and perceptual limitation. These are novels of great, poetical richness (with moments of great humour, it should be added), which bear repeated reading.

![]()

Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue centres around a record shop dealing in jazz, funk and soul in Oakland, California. Its name, Brokeland Records, clearly invites some kind of state of the nation comparison. The novel, rooted in a singular place and concentrated span of time, is an anti-epic, the opposite of his last novel of this size, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Klay, which engaged directly with the grand sweep of twentieth century history. It’s the story of the two men, one Jewish (Nat), one African-American (Archy), who run the store, and also of their partners (Gwen and Aviva), who are midwives supervising home births, and Nat’s son Julius and his friend Titus (who it turns out, perhaps unsurprisingly in this dynastic family drama, to be Archy’s forgotten son). Both sets of adults represent the individual character of a particularised spirit of localism, the historically continuous heart of an area. Both face threats from corporate hostility and competition; the women from the insurance company funded hospital, and the men from the proposed building of a new mall, incorporating its own record shop designed, in parasitic Starbucks style, to replace the original. The story imaginatively magnifies its seemingly small scale setting with a wealth of popular cultural references, creating a sense of universality, of connection with a wider world. It also gives the sense that the problems which these two families have, both on a personal, social and economic level, connect with the concerns of modern society at large. Pop culture is seen as a uniting force (as it is in the essay The Amateur Family in Chabon’s recent essay collection Manhood for Amateurs), bringing together families, communities and otherwise disconnected individuals. Here, jazz and black American music of the post-war years forms the central connection and source of obsessive amateur scholarship (I particularly like the reference to the pipe once owned by Archie Shepp, and winced when Nat, in one of his rages, threw a rare Sun Ra LP on Saturn Records across the room to crack against the wall), which might leave some of the references obscure to many (but then what’s the internet for, after all). There are plenty of references to Star Trek, blaxploitation and martial arts films, the Avengers, Asimov’s Foundation novels and many other cult artefacts thrown in along the way as well. Obama has a presidential walk-on part, and a certain intertextuality is present in the return of the grey parrot from Chabon’s short novel The Final Solution, in which he introduced an elderly, retired Sherlock Holmes into the period of the Second World War. The parrot sits on the shoulder of the Hammond organ playing character Cochise Jones, as if he were some kind of jazz pirate.

![]()

Samuel Delany’s Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders (the title a reference to an unfilmed scene from the original King Kong, re-introduced by Peter Jackson in his remake) is a sprawling novel which bears comparison in its extravagant length to his 1975 novel Dhalgren, which in itself marked a significant change in direction (and was a key book of my teenage years). It’s certainly a long way from The Fall of the Towers trilogy (published 1963-5), which was the first Delany I picked up (in Hay on Wye on a childhood holiday in Wales), a relatively conventional if poetically written science fiction novel. There are still SF elements in the current novel, which proceeds from the present day some seventy years (a lifetime) into the future. But the focus, as in Delany’s recent novels The Mad Man and Dark Reflections, is almost wholly on the physical manifestations of desire, and the utopian vision of a world in which its manifold varieties are accepted and catered for in mutually supportive communities of caring and generous people (men in this case, as the sex is exclusively gay). As much of a fantasy as the early SF perhaps. Changes in the nature of the world, social and technological (the two affecting each other) are noted, but remain in the background, although the society within a society in which the novel takes place is a model of wider transformations. At heart, this is a love story, however, a story of a lifelong partnership between its two main characters (one black, one white): Eric and Morgan (or Shit as he’s more generally, and affectionately, known). The concentration on intricately and delicately detailed sexual encounters, the nature of which might often be construed as disgusting, is shocking at first, but the very compassion and kindness of those involved, and lack of aggression or coercive hostility in any of the participants make it seem, in the end, the most natural thing in the world. A respectful and mutually beneficial means of communication and physical satisfaction in which everyone’s needs, no matter how unconventional, are respected. A key quote from Samuel Johnson, written down for Eric by his gay ‘uncle’ Bill, reads ‘he who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man’, to which he appends the comment ‘but note the good doctor said “beast”, not “animal”. For he who forgets the animal he is, has taken the first step toward becoming a beast’. This undeniably challenging novel also marks a geographical shift for Delany, moving out of the cities, and the suspended apocalypse of Bellona in Dhalgren, and into a remote rural setting on the coast of the US southern state of Georgia. As such, it takes its place in the tradition of American rural utopianism. Perhaps Thoreau would have approved.

![]()

Another favourite author published a new novel this year, Tim Powers’ Hide Me Amongst the Graves being a follow up to his The Stress of Her Regard, published some 23 years earlier in 1989. Again, I re-read the first novel again in order to enjoy the stories as a cohesive whole. Whether the new book can be appreciated without first having read the earlier one is dubious. It’s certainly preferable to read both. I’ve looked at them in more detail

elsewhere, so suffice to say that Hide Me Amongst the Graves was a thoroughly satisfying follow up, taking Powers back to the Victorian London of his best known work (and a founding novel in the steampunk subgenre) The Anubis Gates. The typically dense and thoroughly worked out mythology common to both novels brings together a comprehensive collection of Romantic and gothic device, which are rationalised around the central notion of a mineral race, stony creatures of the earth, which predates humanity, and which, in its vestigial form, still preys parasitically upon it. They form close and, in their own murderously jealous way, loving relationships with particular individuals, and bring with them, as a side effect, visionary insight which feeds into artistic inspiration. They are like bloodsoaked muses. The novels ingeniously incorporate vampires, lamiae, golems, ghosts and many other supernatural manifestations into their overarching mythological schema, and also use the Romantic and Aesthetic poets as major characters, commenting on their lives and the nature of their inspiration in the process: Keats, Shelley, Byron, Polidori, Mary Shelley and Edward Trelawny in The Stress of Her Regard, and Dante Gabriel and Christina Rossetti, Algernon Swinburne and a returning Trelawny in Hide Me Amongst the Graves. Powers also evokes the haunts of the Romantics very atmospherically, from the Alps, Venice, and Ligurian coast of the first novel, to the gaslit London of Hide Me Amongst the Graves, with its hidden and labyrinthine subterranean subcity.

![]()

Also this year, I read Kim Newman’s highly entertaining Moriarty: The Hound of the D’Urbervilles (how can you resist a title like that), a series of tales in which the Napoleon of Crime’s righthand man, the proudly thuggish Colonel Sebastian Moran, relates several of the classic Sherlock Holmes stories from the villain’s perspective, revealing Moriarty’s hand to be evident in more cases than Watson gave him credit for. Holmes here becomes less deductive genius, defending crown and country from international villainy, more an irritating meddler ruining carefully laid plans of beautifully elegance and consummate wickedness. Wicked and its follow up Son of A Witch by Gregory Maguire were brilliant expansions of the Oz mythos, making of the childhood tales something wholly adult. Maguire uses his recasting of L Frank Baum’s world to reflect upon the pains of growing up, of being visibly different, as well as to comment on modern politics, religion and the uses and abuses of power. These were novels which really surprised me. I expected them to be relatively throwaway entertainments (and there’s nowt wrong with those), but they turned out to be something much deeper (whilst still being hugely entertaining).

![]()

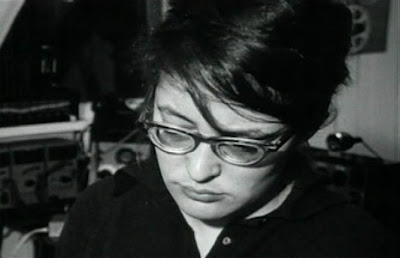

I also read James Knowlson’s comprehensive life of Samuel Beckett, Damned to Fame, which offered fascinating insights into his role in the French resistance during the war. I look forward to seeing some of the

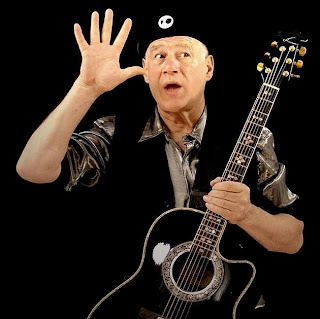

Bike Shed Theatre’s Beckett season in Exeter in the new year. Throwing Muses singer and songwriter Kristin Hersh wrote something which went well beyond the standard rock autobiography in Paradoxical Undressing, offering an intimate, impressionistic and beautifully written account of her early life which read more like a novel. Finally, Barry Miles’ London Calling was an enjoyable account of the post-war counterculture in the capital, from Soho soaks, penniless poets and savage artists of the Bacon, Freud and Dylan Thomas era, to those of the YBA generation. In between, he ranged over the artistic and radical political spectrum, from jazz lovers, British beats, Mods, pop artists, hippies and revolutionaries to punks, industrial noisemakers and new romantics. He spends the greatest amount of time in the 60s. Here, his observations benefit greatly from his own direct involvement in the scene, having worked at the Better Books shop in Charing Cross Road, co-run the Indica Gallery where John Lennon first met Yoko Ono, and helped launch the countercultural newspaper International Times. Miles also writes about Michael Moorcock, J G Ballard and New Worlds, and two figures I’ve become familiar with this year:

Pauline Boty (whom he describes as ‘the purest, and perhaps the best, of the British pop artist of her time’, with ‘none of the dull masturbatory “male gaze”of the male pop artists’) and

Bruce Lacey, theatrical prop maker, antic performer, robot controller and general madcap goon. It’s a fascinating story, with Miles customarily unafraid to make moral judgements, and shows what a rich and fertile ground the city has been for artists wanting to go against the grain.