Some interesting stuff has made it onto the Oxfam online shop from the Exeter Oxfam Music and Art HQ, courtesy of yours truly and my backroom compadre Kevin. It features delights from the well-lit rooms of pop and jazz, as well as more obscure fare skulking in the shadowy corners. The 1972 LP The Seven Ages of Man, a kind of progressive soul jazz concept album, has a nice cover illustrating the stages of life via 15th and 16th century woodcuts by the likes of Albrecht Altdorfer and Hans Holbein. It boasts an intriguing mix of top class British jazz and soul musicians, many of whom worked tirelessly as session players, but who here have the opportunity to take to the spotlight. I say British, but in fact the stellar quartet of backing singers all came over from America to forge substantial careers in these isles. Pat (better known with the initial prefix PP) Arnold travelled to the UK with the Ike and Tina Turner Soul Revue and stayed to record a number of records on Immediate, with labelmates Steve Marriott and Ronnie Lane of the Small Faces writing a number of songs for her. Doris Troy also came to Britain from the US, making the transition from singing with soul legends like Solomon Burke and The Drifters to providing backing vocals for a diverse array of countercultural artists, from Pink Floyd and the Stones to Vivian Stanshall and Nick Drake (she sings with PP Arnold on Poor Boy from the Bryter Layter LP). New Jersey born Madeline Bell (her first name misspelled on the back cover) was a longtime vocalist for and friend of Dusty Springfield, as well as a solo artist in her own right and member of early 70s pop group Blue Mink. Rosetta Hightower was a member of the 60s American girl group The Orlons before crossing the channel, where she recorded with the likes of John Lennon and Joe Cocker. Lead vocals on the album are taken b Perry Ford and Kay Garner. Ford was in the 60s British vocal trio The Ivy League, who had a number of hits and also provided backing vocals on The Who’s first big single I Can’t Explain, before Pete Townshend and John Entwhistle made it clear that they were up to the job themselves. Garner was a tireless session singer who also worked with Dusty, and many, many others, as well as being one of vocal trio The Ladybirds, who had the dubious pleasure of being regularly featured on the Benny Hill Show. Her voice also graces many an advertisement from the 70s and 80s.

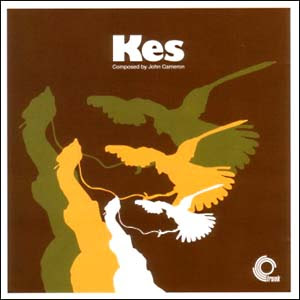

On tenor sax and flute we have Tony Roberts and Harold McNair. Roberts worked with folk and jazz double bass player Danny Thompson in several contexts over the years, from his 1967 trio with John McGlaughlin through to his later fusion group Whatever (and that’s jazz-folk rather than jazz-rock fusion). He also played on several records by Thompson’s fellow Pentangler John Renbourn, including the early music flavoured The Lady and the Unicorn and The Black Balloon, on whose title track he played some exquisite flute. He was also involved in several incarnations of Ian Carr’s seminal 70s jazz-rock group Nucleus. Jamaican born McNair had the privilege of playing with Charles Mingus when he came over to Britain in the early 60s. He bridged the worlds of jazz and pop, adding his impressionistic flute lines to a number of Donovan tracks and playing on numerous other records. He also created the gorgeous pastoral moods which added such emotional impact to Ken Loach’s film Kes, his flute tracing the swooping and diving flight of the kestrel. Thankfully, this soundtrack was released a while back on Trunk Records. Sadly, McNair was dead by the time the Seven Ages of Man record was released, having passed away in 1971 at the terribly premature age of 39. Bassist Brian Odges played with Michael Gibbs and was part of the group, alongside Tony Oxley and John Surman, on John McGlaughlin’s classic 60s jazz LP Extrapolation. He was another session musician who pops up in all sorts of surprising places, from James Bond soundtracks and Goodies LPs to The Walker Brothers 1978 LP Nite Flights, which saw the beginning of Scott’s artistic renaissance. Pianist Gordon Beck, who also provides some of the string arrangements, was another element in Nucleus, and played in Tubby Hayes’ groups in the 60s.

Talking of Tubby, one of the monumental figures on the 60s jazz scene, we have a re-release of his 1964 LP (under the guise of the Tubby Hayes Orchestra) Tubbs’ Tours. This was put out on the Mole Jazz label, the publishing branch of the late lamented record shop which was over the road from Kings Cross Station and the Scala cinema (also long gone, although still operating as a nightclub and music venue). The label features their wonderful logo, a mole in check trousers and braces blowing hard on his tenor sax. Despite the title, this isn’t a live record. The tours are in the mind only, and refer to a loose theme taking us on a whirlwind trip around various corners of the world. Hence we have The Scandinavian, the flute melodies of Raga, Parisien Thoroughfare, Sasa-Hivi (it’s complex time signature pointing to an African influence) and Israel Nights, before they bring it all back home to identify The Killer of W.1. Tubby takes up his tenor and flute, but also demonstrates his percussive talents on vibes and tympani. Other members of the big band include Jimmie Deuchar on trumpet and mellophonium (a horn associated with the Stan Kenton band), and tenor titans Peter King and Bobby Wellins (who created the legendary solo on Starless and Bible Black on Stan Tracey’s Under Milk Wood LP). More driving hard bop comes courtesy of a reissue of Jackie McLean’s 1965 Blue Note LP Consequence, on which he is egged on by ever-energetic trumpeter Lee Morgan, and supported by pianist Harold Mabern, bassist Herbie Lewis and Ornette drummer Billy Higgins.

Veering off on more abstract improvisatory paths, Paul Rutherford’s 1978 LP Neuph is in the understandably underpopulated genre of solo trombone (and euphonium) albums. I say solo, but there is in fact one short duet here – his dog joining in rather with a rather mournful whine to accompany some trombone thoughts, which be may be a canine idea of musical euphony, or simply an indication that a bowl of Pedigree Chum is required. Rutherford (who is familiar to a couple of folks working here from South East London days of yore) was a mainstay of the 60s and 70s British improvisation scene. He played in a trio with double-bass wrangler Barry Guy and guitarist Derek Bailey, was a temporary part of John Stevens’ ever-shifting Spontaneous Music Ensemble, a key component of the London Jazz Composers Orchestra, and a founder (along with Bailey and Guy) of Iskra 1903. The latter displayed his radical left-wing inclinations, Iskra (or The Spark) having been a revolutionary newspaper edited by Lenin in the early 20th century. He did this for a while from a small office in Clerkenwell, now enshrined in the Marx Memorial Library. The LP uses overdubbing to achieve a layered sound, allowing Rutherford to build up a compositional bed over which to improvise, or simply to have the pleasure of playing with himself. The whole record acts as a showcase for his extended techniques and finely tuned ear for lower end musical textures.

Rutherford’s approach circled the borderlands of contemporary composition and was congruous with certain post-war modernist trends in classical music. John Cage introduced elements of chance into his compositions, although he tended to shy away from any notions of improvisation. In the classical world, the composer must always be king or queen, the musician the loyal vassal. The Hungarian Amadinda Percussion Group has a bash at his 1940 piece Second Construction, which also contains some prepared piano, with a nail and a piece of cardboard wedged between the strings, which are then played directly, without recourse to the keyboard. There are also pieces by Hungarian composers Istvan Marta (Doll’s House Story from 1985) and Laszlo Sary (Pebble Playing In A Pot from 1978). Marta’s Doom: A Sigh from the Kronos Quartet’s Black Angels LP is one of the most profoundly depressing pieces of music I’ve ever heard (it’s also, in its own expressive way, a brilliant sound picture of despair in a Ceaucescu-era Romanian village). This is somewhat lighter. Also in a cheerful vein are American xylophone virtuoso George Hamilton Green’s ragtime pieces for the instrument, and a different kind of virtuosity is displayed in a number of African traditional pieces.

Another quartet taking an unconventional approach to classical music were the Camarata Contemporary Chamber Group, whose LP The Music of Erik Satie: The Velvet Gentleman was released in 1970 on the Deram Records label, the ‘progressive’ subsidiary of Decca Records. Various Satie pieces, including the familiar Gymnopedies and Gnosiennes and the beautiful and mysterious Pieces Froides, are arranged for flute, oboe, clarinet and guitar, added to which are the new found sounds of the Moog synthesiser. More pioneering Moog sounds can be found on Jean-Jacques Perrey and Gershon Kingsley’s 1967 LP Kaleidoscopic Vibrations, with its retina-dazzling full spectrum op art cover. Perrey and Kingsley had direct access to the source, having been shown by Robert Moog himself how to use his new musical machine. There’s also a bit of Ondioline on there, the instrument immortalised in the title of Stereolab’s epic drone odyssey Jenny Ondioline. A lot of the music is of a rather whimsical cast, with covers of the likes of Umbrellas of Cherbourg, Strangers In The Night and Winchester Cathedral, but the French and German duo do head out into the kosmos for Carousel of the Planets and Pioneers of the Stars.

Electronic music of a more intensely serious nature is to be found on the 1965 Turnabout LP self-descriptively titled Electronic Music. This features John Cage again, with the tape material for his Fontana Mix, recorded at the Studio di Fonologia in Milan in 1958. This was, rather charmingly, named in honour of his landlady in Milan. It was the basis of one of his chance pieces, the score written on a number of plastic transparencies on which geometric images were inscribed. These would then be layered on top of one another, with a grid at the bottom providing a nexus upon which the various graphic elements (lines, points and curves) would intersect. The instrumental combinations were left unspecified (the element of indeterminacy extending beyond the compositional realm), and the sleeve notes tell us that versions were performed by David Tudor for amplified piano, Max Neuhaus for percussion and guitar by Cornelius Cardew. Cage was invited to the Milan studios by Bruno Maderna and Luciano Berio, and the second side of the LP is taken up by Berio’s 1961 piece Visage, also recorded at the Studio di Fonologia. This is an extraordinary work (which I've written about before), harrowing and hilarious, sensuous and harsh, with bewilderingly swift transitions between states. At the centre of it all is the remarkable voice of Cathy Berberian, Berio’s wife at the time. Her performance explores the whole range of human emotions and vocal sounds, and takes us into the whirling maelstrom of a troubled subconscious. From the other side of the Atlantic, and the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Centre, we have Turkish composer Ilhan Mimaroglu’s Agony, a representation in electronic sound of Armenian painter Arshile Gorky’s painting of the same name. The piece is appropriately fierce and fragmented, with mechanical explosions, sirens and eruptions depicting a noisy zone of conflict, either external or internal.

There’s more modern classical music on an LP by the Speculum Musicae chamber group, who play pieces by American composers Donald Martino (Notturno from 1973) and Charles Wuorinen (Speculum Speculi, or Mirror of the Mirror, from 1972). These pieces in some ways mark the last hurrah of musical modernism in America. There’s a steely and prideful defiance in Wuorinen’s sleevenote definition of his and Martino’s compositions as ‘demanding contemporary music’. He acknowledges the primary influence of Milton Babbitt, who embodied the abiding intellectualism of 50s and 60s classical orthodoxy in America – music as theoretical mathematics and advanced calculus, the marks of the score as important as their audible realisation. His infamous remarks about not being concerned as to whether his music had an audience was taken out of context (the title of the article in which it appeared, Who Cares Who Listens?, was not of his choosing), but nevertheless pointed to a certain indifference to the reception of his work beyond the insulating walls of the academy. As for notions of popularity, there was a definite sense that this was a music of almost monastic seriousness, and that it had somehow failed if it afforded any immediate pleasures. There’s actually something retrospectively refreshing about this purity of intent, although the attendant snobbery and elitist disdain for any music which didn’t conform to the new and rigidly defined ideal is less admirable. Doctrinaire artists of this stripe seem intent on refuting any other path, as if there can’t be a plurality of forms co-existing at the same time. What a narrow and dull cultural world they seek to bring about. Wuorinen’s view of the total serialism of the post-war years, as proposed and practiced by the likes of Boulez and Stockhausen, is almost mystical in its belief in its essential rightness. He observes of himself and Martino that ‘in our dissimilitude we bear witness to the inexhaustible treasures of our common patrimony – the twelve tone system’. An illuminating use of the word patrimony there. This was a rigorously abstract and unemotional music which rejected what it saw as the ‘soft’ feminine stylistic attributes of open expression. Female serialists are certainly thin on the ground (mind you, female composers of any sort are not exactly numerous at this point in time). Wuorinen is ultimately generous in ceding control of his music, however. He refuses to overdetermine its meaning or dictate the way it should be listened to, unlike control freaks in the Stockhausen mould. His sleevenotes come to the conclusion that the responsibility for appreciating the music lies with the listener, and he finishes with the observation that ‘once a work has left its maker, it follows its own life’.

The austerity of works in which every element of composition was subject to serialist calculation was somewhat offset by the unusual instrumental colours which were often employed. Percussion frequently came to the fore, and in Wuorinen and Martino’s works we have vibraphone, marimba, xylophone, glockenspiel, temple blocks and gongs. Unusual wind instruments are also used – contrabass, bass clarinet, alto flute and piccolo. There wasn’t much point in making a dramatic break from old symphonic or sonata form conventions if you were going to continue to use the same orchestral colours (and electronic music played an important part here, too). Pierre Boulez’s 1957-62 piece Pli Selon Pli (Fold Upon Fold) also uses an unusual chamber configuration of soprano, mandolin, piano and guitar. Boulez was the belligerent and unrelentingly doctrinaire godfather of hardline total serialism, intent on getting his way and liable to sulk if he didn’t. In this 1969 recording on CBS he conducts the BBC Symphony Orchestra in the outer orchestral sections. The quartet interludes, which set fragments of poetry by Stephane Mallarmé, are folded into the embedding orchestral parts. The choice of Mallarmé’s lush symbolist verse is an odd one, its sensuality perhaps designed to provide a lyrical counterpoint to the dry asperity of the music. Like many of his pieces, he took ages to finish it (and may yet decide it needs a bit more work). For one who often seemed so arrogantly self-assured in his pronouncements on the correctness or otherwise of musical forms, he seems peculiarly insecure when it comes to his own work.

From Boulez to Cant. Is there any possible connection between the two? There’s always a connection between anything in the universe on some level, but I’m at a loss here. The juxtaposition of tweedy Pierre (looking uncharacteristically warm and friendly on the cover, it has to be said) and the gaily-shirted and sailor-capped Brian Cant on the cover of Hey You – Songs from Play Away is a naturally funny one, though. The classic line up joining the irrepressible Brian here are pianist and musical arranger Jonathan Cohen, ex-folkie Toni Arthur, former chart topper with the Four Pennies Lionel Morton, and future Evita Julie Covington. They invite you to enjoy them in A Rollicking Round, try your hand at The Luck of the Game, guess What Is It?, dream of the Broadway Twilight and singalong to the old Play Away theme tune.

Toni Arthur’s darkly atmospheric 60s folk records with her husband of the time Dave Arthur, Morning Stands on Tiptoe, The Lark in the Morning and in particular Hearken to the Witches Rune have recently found renewed favour, their focus on the supernatural elements of traditional music and custom blending perfectly with the sensibilities of modern psych folkies. Original psych folk in the Incredible String Band mould coming out of the unlikely and far from witchy environment of Coventry (which does contain the word coven, mind) can be found in a comprehensive compilation of Dando Shaft material on See For Miles Records. The Shaft featured the vocals of Polly Bolton, who has gone on to become a fine traditional singer, whether solo or alongside Albion Band incarnations, the late Bert Jansch or Alan Stivell. She also made an adventurous duet album, View Across the Bay (which I came across in the shop a few months back), with free improv saxophonist Paul Dunmall (a longtime member of Keith Tippett’s Mujician quartet) who also played his Northumbrian pipes for the occasion, as well as picking up ocarinas, Asian harmonicas, shawms, low whistles, recorders and something called a pregnophone.

The double LP compilation The Walker Brothers Story on Philips Records contains a couple of sublime Scott b-sides which anticipated his classic quartet of 60s solo albums. Archangel is the lyrical precursor of Angels of Ashes, with the big choruses of Such a Small Love and Montague Terrace In Blue. Mrs Murphy is a condensed kitchen sink movie, the L-Shaped Room, A Taste of Honey and This Sporting Life compressed into a 4 minute pop song, its lyric switching cinematically between different viewpoints. Scott gets all existential on In My Room, Spanish songwriter Joaquin Prieto’s study in gloomy introspection which has also been covered by Marc Almond on his Torment And Torreros album with the Mambas. An avowed Scott fan (he wrote the notes for one version of the Boy Child compilation a while back), he was perhaps introduced to it via this version.

Scott would no doubt enjoy the Albert Camus spoken word 10” Albert Camus Vous Parle. Albert addresses a few introductory words to the listener, and reads an 11 minute extract from Cure favourite L’Etranger (The Outsider). There’s also a 10 minute scene from the play Le Malentendu (The Misunderstood) with Alain Cuny, who appeared in films by Fellini (La Dolce Vita and Satyricon), Bunuel (The Milky Way), Jean-Luc Godard (Detective) and Louis Malle (Les Amants), and Maria Casares, the princess Death in Cocteau’s Orpheé. Actor and chansonnier Serge Reggiani reads a bit from the story Les Amandiers too.

Finally, we have a 12” on the old Russian Melodiya Records of the Soviet National Anthem, given the full martial blast on the A side, with what I suppose amounts to a remix on the reverse. I love the idea of this going out on the shop floor to nestle between 12” singles by Wham and Madonna (and below the Metallica one currently on display). Therein lies the conclusion to the cultural battles of the cold war – a historically inevitable victory in the long run.