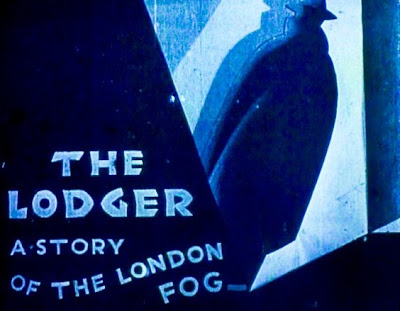

The cinema was mainly a place to see re-issues for me this year, generally travelling the country courtesy of the bfi. Quai des Brumes, Marcel Carne and Jacques Prevert’s fatalistic dockside romance, its digitally clarification thankfully leaving the fogbound atmosphere intact. Jean Gabin possessed an offhand, Bogart-like everyman charm as the disaffected anti-hero, lost in his own existential fog, but offered the chance of salvation through the luminous-eyed Michele Morgan, a young innocent beset by corrupting forces, who persuades him that this isn’t the end of the road after all. A supporting cast of beat barmen, suicidal poets, dedicated and saintly soaks, predatory ‘uncles’ and cowardly petty gangster bullies add to the self-conscious and very French tenor of this nocturnal world, all beautifully shot in moody black and white. The Lodger was also a fogbound film, London smog swirling through Hitchcock’s street sets in this London set thriller, his breakthrough film from 1927. The elegant, sad-eyed Ivor Novello (whose charming music was the subject of a Simon Callow narrated Prom in the summer) provided the model of the ambiguous Hitchcock protagonist, suspected of the murders carried out in the area, but appealing to the female lead nonetheless, and presented as an attractive character to the audience. Hitchcock later encouraged the view that this was his first truly characteristic film, and it had many assured and imaginative directorial touches. Novello’s initial entrance, face swathed in a scarf and topped with a broad-brimmed hat, leaving only his expressive eyes visible, made him seem like a character from one of the German expressionist films which Hitchcock admired so much. Malcolm McDowell’s entrance in Lindsay Anderson’s If… would seem to be paying homage to this scene. The sound of Novello’s character’s restless pacing across the upstairs flat was represented by making the ceiling at which the suspicious landlord’s family and policeman friend transparent, another nice expressionist touch. Nitin Sawhney’s new score was fine, except when he introduced two songs to soundtrack romantic scenes. The introduction of a contemporary pop sound seemed a misjudgement, raising the unfortunate spectre of Giorgio Moroder’s pop video mangling of Metropolis.

Plague of Zombies and Quatermass and the Pit were both great, concise Hammer films from the prolific mid-60s period. It would have been good if they could have been shown in double bills reproducing the conditions in which they were originally shown. The digital restorations made the vivid colours really come to life, and revealed details which had previously remained obscure, such as the posters for other Hammer films on the walls of the tube station corridors in Quatermass and the Pit (Dracula Prince of Darkness, The Nanny and The Witches, the other film which Nigel Kneale scripted for the studio at the time). Plague of Zombies’ famous dream sequence came over in all its queasily tinted glory, and Jacqueline Pearce’s performance remained impressive and affecting. Quatermass and the Pit was by far the best of Hammer’s Quatermass adaptations, with Andrew Keir’s Scottish professor hugely preferable to Brian Donlevy’s lame American tough guy. The stagebound London street and underground sets were impressive, and if some of the effects were rather exposed on the big screen and with the new digital clarity, it didn’t really matter. Barbara Shelley was as great as ever, particularly in her electrifying levitation scene, and there was a very effective score by Tristram Cary, including some unnerving pulsing and howling electronic sound.

Carl Dreyer’s 1955 film Ordet was an incredibly powerful experience, its emotions magnified on the big screen. Its concentrated sense of place, and of weather, and its intimate observation of family and small community relations also came through with more clarity in the cinema, which allowed for a greater absorption in its constrained environment. The final scene is one of the most moving in all cinema, a miraculous resurrection which restores to life the woman who is the balancing heart of the family. It is both spiritual and very physical (the husband and wife Mikkel and Inger’s passion for one another is clearly evident, revealed in small gestures), the close-ups revealing their embrace in all its saliva and snot dripping emotional intensity. The messianically deluded Johannes, an utterly mesmerising performance by Preben Lerdorff Rye, is a mystical presence throughout, his madness an ambiguous blend of the genuinely visionary and the mental fractured. It’s perhaps the greatest religious film in the history of cinema.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Husbands was John Cassavetes’ long-gestating and highly personal portrait of friendship, self-delusion and mid-life crisis. It’s a film which is unapologetic in its honest and unflattering examination of male behaviour, and it drew directly on the feelings and experiences of its three main actors: Cassavetes himself, Peter Falk and Ben Gazzara (the latter of whom died earlier this year). All three became completely absorbed in the creation and inhabitation of their characters, and a real and lifelong friendship was forged during the filming. As for new films, Berberian Sound Studio was the standout for me, centring around a quietly commanding performance by Toby Jones (recently seen playing Alfred Hitchcock in the TV movie The Girl). The claustrophobic limitation to dimly lit studios and hotel rooms gave it a very interior feel which, as Julian House’s characteristically potent poster design suggested, reflected the story’s excavation and exposure of the reserved protagonist Gilderoy’s psyche. The fetishistic lingering over the dials and switches of the analogue equipment highlighted the sonic element which was so integral to the film, and it was also blessed by an atmospheric score by Broadcast. The film has just been released on dvd, and Broadcast’s soundtrack will by released on the 7th January. Two Days in New York, Julie Delpy’s follow up to Two Day in Paris, had considerable charm, largely due to the presence of Delpy and her co-star Chris Rock. The French family’s arrival in America pushes the original’s acerbic and surprisingly unflattering portrayal of Delpy’s home country and its culture to new and excruciating depths. I’m looking forward to her return in 2013 as Celine in Before Midnight, Richard Linklater’s Greek-set follow up to Before Sunrise and Before Sunset.

Away from the cinema there was more Hitchcock in the form of Sabotage, his downbeat English thriller with the famous boy with a bomb on a bus scene – still shocking to this day; and the picaresque American ‘wrong man’ chase adventure Saboteur, with its Statue of Liberty finale presaging North by Northwest in its ‘dangling from a famous monument’ cliff (or torch) hanger. Young and Innocent, a lesser known 1937 English picture, was another wrong man on the road searching for the real killer thriller, light and jokey in tone. The long crane shot tracking through the seaside hotel at the end, finishing with a close-up of the killer’s eye, its twitching the detail betraying his guilt, is justifiably renowned. I rediscovered David Lynch, having unexpectedly been mesmerised by Inland Empire, three hours of undiluted dream logic which were a superb distillation of his surrealistic essence. As a result I went back to see Lost Highway and Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, which possessed this essence in smaller doses, along with the small town teen dramas and generic elements which I find less compelling. Kelly Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy and Meek’s Cutoff were both excellent, quiet and slow-paced anti-dramas with considerable cumulative power. The former in particular was an almost unbearably moving story of one woman searching for her missing dog, reminiscent of Robert Bresson in its distanced by compassionate focussing on small detail and rejection of grand or melodramatic expressions of emotion.

There was some good Czech stuff, including Frantisek Vlacil’s magisterial medieval epic Marketa Lazarova, the similarly evocative Valley of the Bees, set in the same historical era, and the 1970 film Adelheid, a ‘haunted house’ story in which the ‘ghost’ is a living German woman. In the post war period, she is forced to become the housekeeper in the large, empty house which was once her home. Mala Morska Vila (aka The Little Mermaid) was Karel Kachyna’s beautiful and surreal 1976 retelling of the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, with wonderful costumes (and hairstyles) and a great score by Zdenek Liska (released on Finders Keepers Records). Milos Forman’s 1967 freewheeling comedy of bumbling official incompetence Fireman’s Ball was unsurprisingly the last he made in his native Czechoslovakia, and was shot by Miroslav Ondricek, just before he went off to work on If… with Lindsay Anderson. Some of the female actors who make brief appearances (this is largely a film about foolish men) are familiar from Forman’s earlier Loves of a Blonde, and Vera Chytilova’s Daisies. The 1972 film Saxana (aka Girl on a Broomstick) was good fun, and the soundtrack is once more available on Finders Keepers.

Other highlights included: Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s bewitching Buddhist fantasies Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives and Tropical Malady; Terence Davies’ translation of Terence Rattigan’s play The Deep Blue Sea into his own inimitable style, with a fine central performance from Rachel Weisz; Roman Polanski’s rain and bloodsoaked Macbeth; Chris Marker’s La Jetee and Sans Soleil, watched in tribute to the French director who died this year; Jerzy Skolimowski’s 1970 film Deep End, set in Soho and a dilapidated East End swimming bath, and released in the bfi’s Flipside series; Wim Wenders’ Wrong Move and Until The End of the World, the latter clearly a huge self-indulgence, but I can’t help liking it anyway; Andrew Kotting’s Ivul, a fable about a boy who decides his feet will never touch the ground again, and travels across the treeline; Pasolini’s Accatone and Medea (with the Masters of Cinema releases of Porcile and Hawks and Sparrows awaiting); Michael Powell’s late, Australian-set portrait of an artist and his muse (played by James Mason and a teenage Helen Mirren) Age of Consent; Mario Bava’s Blood and Black Lace, a highly stylised giallo (not usually a subgenre I have any liking for) and the deeply strange, Christopher Wicking-scripted Scream and Scream Again, a 1970 horror film which blends swinging sixties clubland nightmare with the neo-Nazi genetic engineering of brutal superbeings, and which features the ever-interesting Michael Gothard as a psychotic hippy; Jacques Demy’s bizarre but colourful musical A Slightly Pregnant Man (a typically hangdog Marcello Mastroianni, here married to Catherine Deneuve’s hairdresser); the wonderful The Ghost and Mrs Muir, with its lovely Bernard Herrmann score, an old favourite; Paul Kelly’s Saint Etienne-produced semi-fictional look at the pre-Olympic Lea Valley What Have You Done Today Mervyn Day?; Light Years Away, a strange allegorical fantasy starring Trevor Howard and Mick Ford which I’d remembered from childhood; Artemis 81, another complex fantasy from the same period, written by David Rudkin; Some great children’s TV fantasy, largely courtesy of the ever-reliable Network – Shadows and Dramarama Spooky (with fine stories by Alan Garner and Susan Cooper), The Boy Merlin, Children of the Stones (again), Escape Into the Night (an adaptation of Catherine Storr’s novel Marianne Dreams, which makes for an interesting comparison with Bernard Rose’s 1988 adaptation Paperhouse), and The Ghosts of Mottley Hall, with the marvellous Freddie Jones on fine blustering form (and he could bluster like no other); some excellent bfi documentary collections – London on the Move, Wonderful London (a fascinating insight into the capital in the 20s), Roll Out the Barrel and Here’s A Health to the Barley Mow; the landmark series 49 Up, observing the lives of a diverse collection of people from various backgrounds over seven yearly periods, which also came to its latest instalment, 56 Up, this year; and of course, a goodly amount of Doctor Who, including Robert Holmes’ hilarious satire of bureaucracy The Sunmakers, and the Pertwee adventure The Ambassadors of Death, available in colour at last and serving as a fitting tribute to Caroline John.